I met Ben McKie in Egypt, in that wide stillness where the Sahara opens the senses and quiets the mind. What began as a chance meeting at a retreat in Siwa Oasis became a longer dialogue about trauma, leadership, service, and the subtle ways environment shapes our inner life. I’ve wanted to bring his voice to this space for a while. This interview does that.

Ben is a consultant psychotherapist whose work moves between clinical practice in London, leadership consulting, and immersive retreats in the desert. He founded a social enterprise with a simple but radical premise: help the people who help others. The idea is practical and human. Make psychotherapy more accessible for the teachers, caregivers, nurses, first responders, and frontline professionals who carry entire communities on their backs—and the benefits ripple outward.

What drew me in is the way Ben integrates multiple languages of healing without turning them into noise. He talks about presence in the room and presence in the dunes. He speaks corporate and Taoism, EMDR and quiet. He doesn’t romanticize the desert; he respects it. He doesn’t chase complexity; he listens for what’s essential.

Why this conversation matters

We are living in a high-friction world where attention is exhausted and nervous systems are overclocked. Many people who take care of others are depleted. In our conversation, Ben outlines a model that is not charity and not self-promotion. It’s an ecosystem. Sponsorships fund low-cost clinical services in London. Those services strengthen the very people who support the rest of us. Profit is not demonized; it’s redirected to create future projects that serve the same mission. It is service designed to scale.

Beyond the model, the interview explores a deeper question that matters to anyone interested in psychology, integration, and personal growth: how much of healing is technique, and how much is condition? Ben’s answer is quiet and provocative. The setting can do more than assist; in certain cases, it becomes the method. He describes how residential, nature-based work removes interruptions and creates the continuity people need to face themselves. The desert, in his words, does a lot of the work.

The desert as a method

You’ll hear us talk about a night under the stars that felt like an entheogenic session without substances. The point is not to replace medicine with scenery; it’s to notice how silence, vastness, and orientation to sky and horizon can re-tune attention and emotion. When someone doesn’t have to commute the next morning, answer messages, or feed the algorithm, the psyche moves differently. Stabilization practices land. Breath has somewhere to go. The environment is not background. It’s co-therapist.

Doing less so more can happen

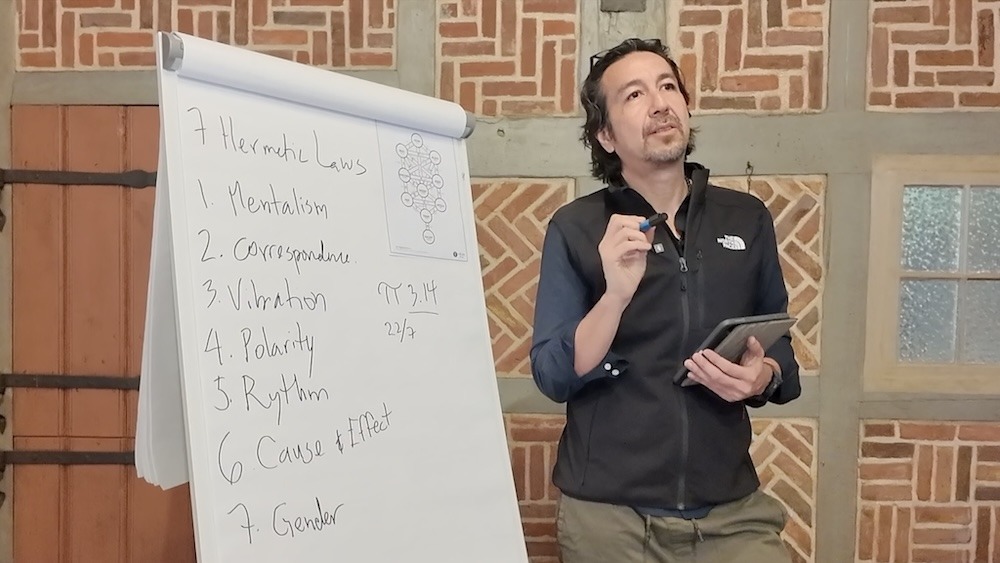

One of my favorite parts of the conversation is Ben’s take on wu wei—non-forcing. In leadership settings, he resists the impulse to pack schedules with content. He removes frameworks so people can meet themselves. When outcomes stop being pushed, attention becomes available for what is actually present. This isn’t passivity. It’s disciplined presence. It’s the difference between performing change and creating the conditions in which change becomes unavoidable.

Embodiment that actually integrates

We also explore how qi gong functions as a bridge between cognition and sensation. Ben describes movement, breath, and unusual postures as anchors that pull attention out of repetitive thinking and into felt experience. Not as a performance, but as orientation. When the body is fully “online,” people return from practice with a different energy—awake, localized, and available. That state travels into group work and one-to-one sessions. Integration stops being a concept and becomes the way a person stands, breathes, and chooses.

Trauma work grounded in nature

Clinically, Ben is pragmatic. He tailors protocols—EMDR, exposure-based approaches, narrative work—to the person in front of him. The point is not brand loyalty. It’s fit, safety, and sequence. He emphasizes stabilization first: meditation, breath, simple practices that recalibrate the nervous system so exposure heals instead of retraumatizes. Do this in the right setting—desert, countryside, lakes—and the work goes further with less strain. The environment lowers baseline arousal and gives the system a place to land.

A life between London and Siwa

There is a human rhythm underneath the professional one. Ben speaks honestly about returning from Egypt to grey skies and rain, noticing resentment, and then experiencing a quiet reframing. Hot shower. His own bed. Work he cares about. Balance replaced the narrative of loss. He doesn’t glorify living in one place forever. He moves between them and carries the qualities of each into the other. That, too, is integration.

Watch the interview

This conversation is for therapists, facilitators, coaches, and leaders who want to serve without burning out. It’s for anyone who senses that context is not a luxury but a variable that decides whether a method lands or drifts away. It’s also for people who are curious about what happens when modern psychology sits down with ancient landscapes and listens.

When the video goes live, you’ll find it embedded here and on my YouTube channel. If the themes resonate—trauma-informed work, embodiment, non-forcing, and the intelligence of place—share the interview with a colleague who might need it this week. And if you’ve spent time in environments that changed you, I’d love to hear your story in the comments.

Related

Discover more from TRANSCENDENT PSYCHOLOGY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.