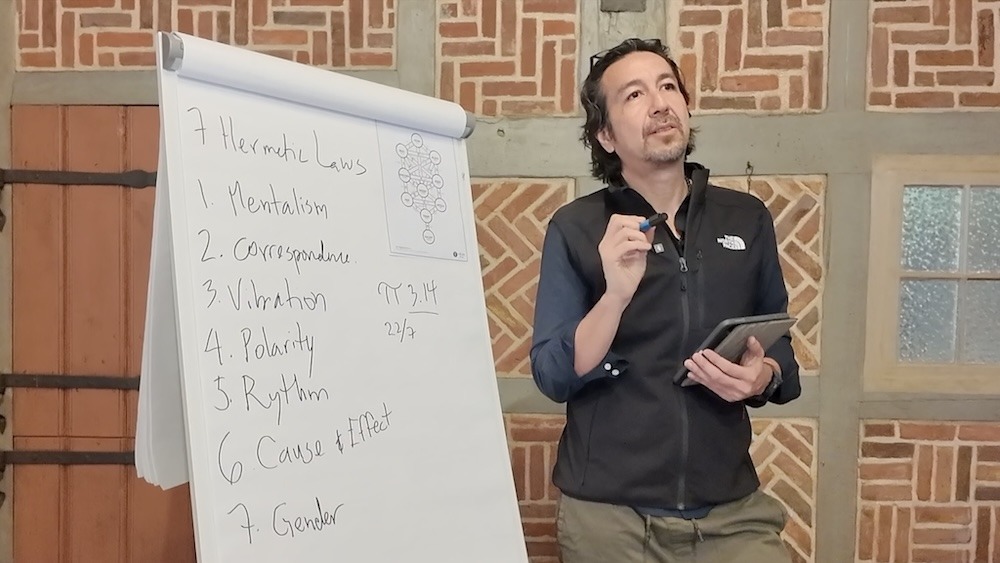

In an age where psychology and spirituality are beginning to speak more fluently with one another, profound bridges are being built between ancient mystical traditions and modern therapeutic models. One such bridge is the resonance between Internal Family Systems (IFS) —a therapeutic modality developed by Richard C. Schwartz— and the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, the symbolic map of consciousness in Jewish mysticism. Though these systems come from vastly different historical and cultural roots, both offer nuanced frameworks for understanding the inner world, the path to healing, and the nature of the Self.

The Multiplicity Within: IFS and the Many Faces of the Soul

IFS posits that the human psyche is not monolithic, but made up of distinct “parts” — inner subpersonalities that carry memories, functions, and emotional burdens. There are Managers, which try to keep us safe by controlling our environment; Firefighters, which react impulsively to avoid pain; and Exiles, the wounded inner children who carry the raw wounds of trauma. At the center of this internal system is the Self, a core of compassion, clarity, and calm that can lead the system with wisdom and love.

This idea of multiplicity may sound modern, but echoes of it appear in mystical traditions as well — and none more richly than in Kabbalah.

The Sefirot as Archetypal Energies of the Psyche

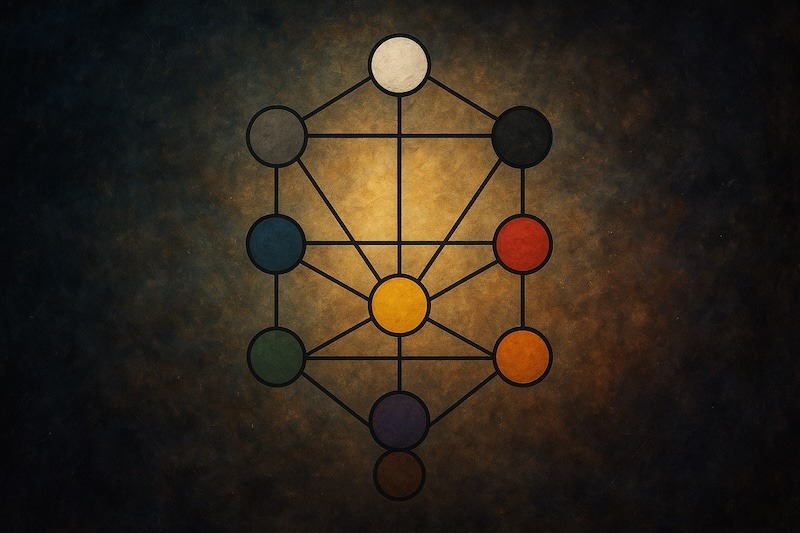

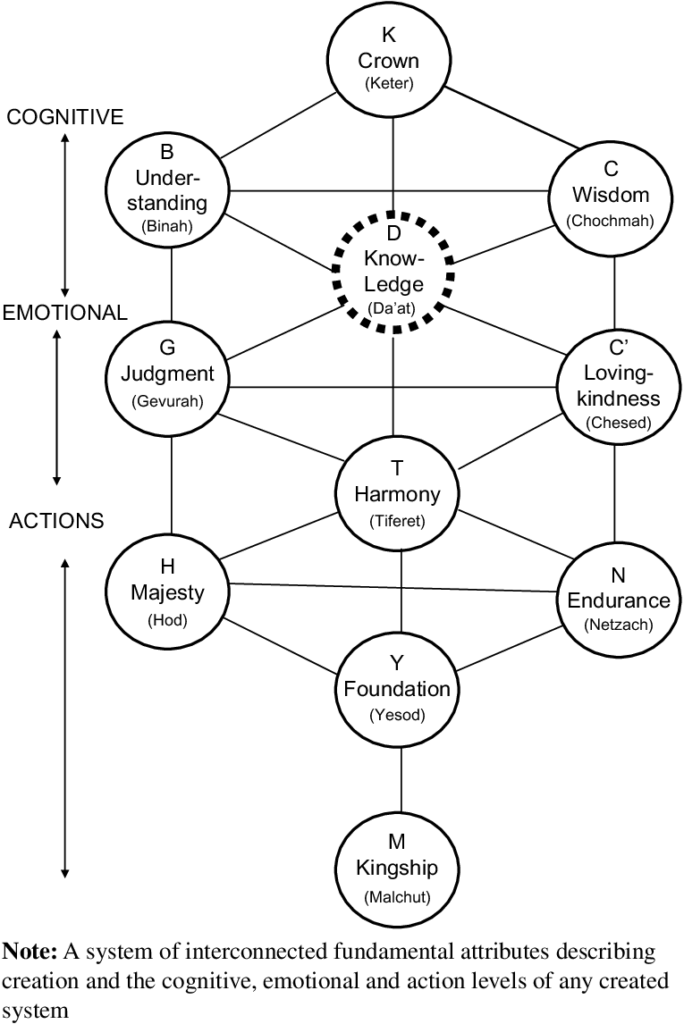

In Kabbalah, the Tree of Life is composed of ten sefirot, divine emanations or attributes that mirror both the structure of the universe and the architecture of the soul. Each sefirá expresses a distinct quality: Gevurá is limit and discipline, Jésed is loving-kindness, Tiféret is harmony and compassion, Yesod is the foundation of identity and connection, and Maljut is manifestation in the world.

These are not merely theological concepts—they are living dynamics that operate within every human being. A person might embody an overactive Guevurá (self-judgment), a collapsed Maljut (disempowerment), or a dissociated Yesod (loss of inner coherence). Just like the “parts” in IFS, these energies can be out of alignment, in conflict, or in need of healing and integration.

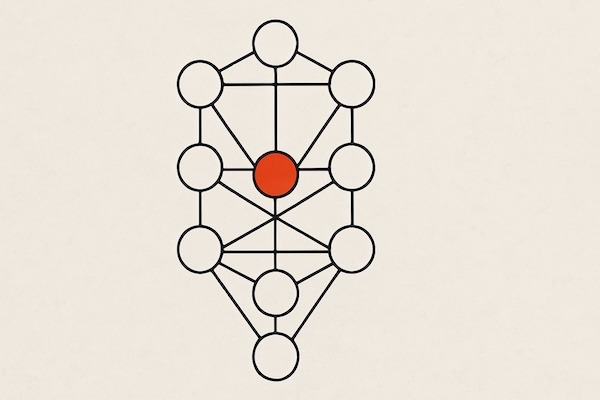

Yesod and the Ego, Tiféret and the Self

One particularly powerful mapping between IFS and Kabbalah lies in the relationship between Yesod and Tiféret. Yesod, often associated with ego, identity, and the interface with the outer world, can be likened to the IFS “parts” — the various personas and strategies we develop to navigate life. Tiféret, by contrast, sits at the heart of the Tree and corresponds to the Self in IFS: it is the seat of divine compassion, balance, and truth. When Yesod is disconnected from Tiféret, the ego acts alone — overcompensating, performing, or protecting. When reconnected to Tiféret, the ego becomes a vehicle for embodied spiritual expression.

IFS offers a therapeutic process to help parts unblend and trust the Self. Kabbalah offers a mystical path in which each sefirá is balanced and harmonized under the central principle of Tiféret — a model of the aligned soul.

Transformation through Integration

In both systems, healing is not about elimination, but integration. IFS does not aim to destroy parts, but to unburden and restore them to their natural roles. Similarly, Kabbalah teaches that the sefirot are holy; imbalance only arises when one dominates without the tempering presence of its complement. Jésed without Guevurá becomes indulgence; Guevurá without Jésed becomes cruelty. The aim is not purity through subtraction, but wholeness through dynamic equilibrium.

This idea resonates deeply with Schwartz’s notion that all parts are “good” — they simply need to be led, not exiled. Likewise, the Tree of Life is not a hierarchy to ascend and leave behind, but a system to be embodied and harmonized.

Descent Before Ascent: The Kabbalistic Path of Healing

Kabbalah emphasizes that ascension requires descent. To rise into the light of Kéter (the crown of divine unity), we must descend fully into Maljut, the realm of matter and shadow. This reflects IFS’s insight that we must turn toward our pain — not bypass it — to heal. The path upward begins with meeting the Exiles, listening to their burdens, and restoring internal trust.

As Mario Sabán writes in Sod 22, “no hay ascenso verdadero sin un descenso completo.” The soul must embrace its shadow and learn from the material world — not reject it. Healing is a spiral, not a ladder.

Toward an Integrative Spiritual Psychology

Both IFS and Kabbalah lead us to the same revelation: we are not broken, we are fragmented. Our wholeness is never lost, only obscured. Through compassion, presence, and deep listening — to both our inner parts and the divine energies flowing through us — we begin to remember who we truly are.

Whether you are a therapist, a spiritual seeker, or someone walking the path of healing, these two traditions offer complementary lenses through which to understand the journey. Psychology and mysticism do not have to contradict; they can illuminate each other.

And perhaps that is the great work of our time: to bring the fragmented pieces of our psyche, our tradition, and our world back into sacred harmony.

Author’s Note: This article draws inspiration from Richard Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems and Mario Sabán’s interpretations of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, particularly in his book “Sod 22: El Secreto.”